Kapampangan vloggers maximize social media use to save their native tongue.

Six-year-old Nicole gets her white dress soiled while playing kurang-kurangan (toy kitchen set) with her cousins in their verdant backyard in the rural town of Minalin, Pampanga on a hot Saturday afternoon.

Without minding the plastic pan, the makeshift stove, and the leaves she cooks; one would think that Nicole is an expert in the kitchen—a trait most of the Kapampangans like her possess.

She pretends to cook sisig, a native Kapampangan dish made of grilled pork ears, liver, chili and calamansi. Nicole prepares another plate where she would transfer the “cooked food”. She seems excited about the finished product. But before she could serve her specialty, her mother called:

“Nicole! Uwi na dito kakain na tayo. Gabi na!”

Despite being born to Kapampangan parents, Nicole doesn’t know how to speak Kapampangan. Her mom and dad talk to her in Tagalog.

“Bang misane la, syempre keng school ampo keng work Tagalug ing gagamitan diba (So they’ll get used to Tagalog since that’s what they speak in school),” Kaye, Nicole’s mom explains.

This practice is one of the major factors why the Kapampangan language is considered to be highly threatened according to Kapampangan linguist and historian Mike Pangilinan. Pangilinan studied linguistics at the Heinrich Heine Universität Düsseldorf in Germany and has devoted his time in the promotion and preservation of the Kapampangan language and culture.

“Mababa la lawe kareng Kapampangan. Reng pengari da Kapampangan la pero balamu ing Kapampangan pota mung mimwa la ampong potang managkas la pero ing everyday communication dapat Tagalug. (They see Kapampangan as a lower language. They just use it when they’re mad or cursing but they speak in Tagalog for their everyday communication),” Pangilinan explains.

‘Dying’ language

In her opinion column at Philstar.com entitled Kapampangan—a dying language, a serious threat to culture and identity published on January 29, 2019, writer and educator Sara Soliven-de Guzman says a language dies when it is only used for oral expression and not as a written language.

Pangilinan however clarified that debates are still going on whether to label Kapampangan as a ‘dying’ language. According to him, at least 75 percent of the population should speak a language for it to survive the next generations.

He says 78 percent of Pampanga’s population uses Kapampangan as their medium of communication. The province has a population of 2,198,110 based on the 2015 Census of the Philippine Statistics Authority.

“Eku sasabyan dying language ne uling dakal ta pa. pero ing question nanung gagawan da reng 78 percent a Kapamangan keng amanu da? Papasa de kareng anak da o ali de? (I won’t say it’s a dying language because we’re still many. But the question is what are we, the 78 percent, doing to our language? Are we passing it to our children?),”

Pangilinan elaborates.

But the possible demise of the Kapampangan language cannot be blamed to Kapampangan parents who speak to their children in Tagalog alone as this is just a result of more complex events in the history.

Robby Tantingco, Director of the Center for Kapampangan Studies at the Holy Angel University (CKS-HAU) says the relegation of Kapampangan as a third language, next to English and Tagalog, can be traced back to the Commonwealth Period when Filipinos were propagating Tagalog as the national language—a form resistance against the American colonization.

He refers to this as the nationalism in language, which resulted in extreme influence of the Filipino or Tagalog language in the media, the school system and professional institutions.

“It was the government that wanted to unify the nation through the popularization of a national history and a national language.” Tantingco says.

The local migration especially in the cities of Angeles, San Fernando and Mabalacat has forced businesses in Pampanga to cater to migrants– making use of Tagalog in most of the establishments. The proximity of the province to Metro Manila which is the center of the Tagalog region is also a factor that led to neglect of other Kapampangans to their language according to Tantingco.

Meanwhile, Pangilinan says the decline in usage of the Kapampangan language started during the time of former president and dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Since Marcos’ political enemies were mostly Kapampangans, Pangilinan says the strongman had intended to demoralize them and get rid of their perceived arrogance.

“Atin talagang deliberate state suppression king kekatamung amanu ampong kultura… Makananu mong a demoralize? Suppress me ing language da keng eskwela, siran mo king media at siguraduan mung ala lang abasa tungkul king sarili da. (There is a deliberate state suppression against our language and culture… How do you demoralize a group of people? Suppress their language, destroy them in the media and ensure that they won’t have anything to read about themselves),” Pangilinan explains.

Staying ‘alive’

Four-year-old Kalia rides her bike around their subdivision in Angeles City. Her father, Kevin Montalbo, follows her with a handy video camera.

“Kalia, kapamu panayan mu ku. Eka mamaligwa video da’ka (Kalia, wait for me. Don’t be in a rush, I’ll take a video),” Montalbo shouts as he runs towards her daughter.

According to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), a child has the right to enjoy her culture, practice her religion and speak her language, whether or not these are shared by the majority of the people in the country.

This is one of the reasons why Montalbo speaks to his daughter in the local vernacular. Unlike Kaye, Montalbo says he doesn’t want to deprive his daughter of her own language. He also believes talking to Kalia in Kapampangan will help in the process of her cognitive development.

“So nung ing anak mu babawal meng manigaral kapampangan, you’re violating her rights (If you are prohibiting your child to speak in Kapampangan, you’re violating her rights),”

Montalbo explains.

Montalbo says there’s no conscious effort on his part to teach his daughter Kapampangan words.

“Kasi common sense mu naman eh, Kapampangan kaming pengari. Maratun ke Pampanga. Ing anak ku, paragulan miya naman keni. Ot Tagalug ing turu ku kaya? (It’s just common sense, we are Kapampangan parents, we live in Pampanga. We raise our child here so why should we speak to her in Tagalog?),” Montalbo says.

But this simple common sense Montalbo is trying to live up is not only limited within their humble home.

Going ‘Lokal’

Montalbo is an online content creator. In 2018, he co-founded We The Lokal – Kapampangan Videos and Vlogs with Bruno Tiotuico. He now serves as the vlogs’ creative director and works closely with Tiotuico, Miguel Campanilla, Nica Remollo and Celine Buensuceso, Morrisey Hans Racca and Boogie Yu.

As of November 2020, We The Lokal has a total of 89,000 followers on Facebook and 9,097 subscribers on Youtube. Their contents vary from topics about Kapampangan food, festivals, and language tutorial – using Kapampangan as their main medium. Their video entitled How Kapampangans Speak in Tagalog now has 52,000 views on Youtube.

Despite being labeled as “the Kapampangan vloggers” and one of the new advocates of the Kapampangan language, Montalbo says they did not really intend to project that image for advocacy nor branding purposes.

We The Lokal is a product of a passionate desire to create something different from their regular job.

“We wanted to come up with something local. Thus, our name… We weren’t sure what the content was gonna be. What we were sure of, however, was that it was going to be relatable to Kapampangans,” Montalbo says.

The group first released a video about the top five best pandesal in Angeles City. Montalbo says it was their first time to meet as a group when they shot that vlog going to five different bakeries in the city one early morning. Because of their chemistry, charm and bubbly personalities, they then started gaining followers from the Kapampangan-speaking region—that includes the whole of Pampanga, parts of Tarlac, Bataan, Bulacan and Nueva Ecija. Today, they have videos in the forms of interviews, skits and even educational clips.

Montalbo adds they just wanted to embrace their own Kapampangan identity and felt more genuine when they did not pretend to be native speakers of Tagalog nor English.

“Little did we know that, with this decision, we were filling a niche in the market that no one knew they needed.” Montalbo says about their move not to venture to Tagalog vlogging which he sees as overly saturated.

According to Montalbo, We The Lokal isn’t really earning much as they don’t monetize their videos on Facebook and their subscribers on Youtube are still few compared to others. He shares they get their funding from sponsorships, merchandise and donations.

“Doing this opened our eyes to advocating Kapampangan culture, language, etc. So, nowadays, yes, we are aware of what we’re doing, and we’d love to continue doing it.”

Montalbo says.

A threat or an advantage

While Montalbo knows that the social media is a global medium, he doesn’t think We The Lokal is wasting this great opportunity to reach a greater number of audience by opting to use a local vernacular.

“It makes us unique and stand out from the thousands of content creators out there. And the Kapampangans are our actual target audience,” Montalbo says.

In the book PLATFORM: Get Noticed in a Noisy World, author Michael Hyatt explains people are more distracted than ever in the internet world. However, finding the right product and right niche will lead to success according to the online expert who pioneered social networking and blogging.

And this is where Montalbo and his group are coming from—creating Kapampangan content for the Kapampangan audience.

Pangilinan also sees the potential of social media to promote the use of Kapampangan language. According to him, social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram have allowed public dialogue pertaining to the use of Kapampangan language to flourish.

He says social media is instrumental in providing a venue for the people to challenge old norms that are detrimental to the Kapampangan language– such as imposing fines to those who will be using the vernacular in schools.

“Ala lang bosis deng memalen bang manguestiun pero karin ya lungub ing social media. Finally, atin muring anak a mag-rebeldi keng makanyan. (Kapampangans don’t have a voice to question these things. This is where social media gets in the picture. Finally, someone stood up against these norms),” Pangilinan says.

The awareness and the free space social media brought did not only benefit the revival of the Kapampangan language according to Pangilinan. In fact, several minorities and indigenous groups in the world like the Berbers of Morocco and the Minangkabau of Indonesia suddenly became empowered in using their respective languages, the linguist says.

“Kabira agagamit de for the first time ing salita da kasi alang mamawal eh (Suddenly they can use their own language because no one prohibits them from doing so),” Panglinan explains.

In her article New Media, New Audiences? London School of Economics Professor Sonia Livingstone stated that the internet has created a different audience behavior. Since it’s a more ‘personal’ medium, Livingstone explained the people felt more connected and empowered on the new media, or what we call now the social media.

‘It has to be social media’

The Center of Kapampangan Studies at the Holy Angel University is also now looking at different ways to promote the Kapampangan language to the youth of today. Tantingco says social media plays an important role in reaching out to the three million Kapampangans scattered all-over the world.

Aside from the traditional media such as books, magazines, tv and radio programs and even movies, Tantingco says they have started using social media in their aim to spread awareness regarding Kapampangan culture and language.

In September 2015, CKS-HAU launched the Bergaño Dictionario, a mobile app version of the Kapampangan dictionary written by Fray Diego Bergaño in 1732. Tantingco says the app is very useful to both native and non-native speakers of Kapampangan. As of September 2019, the app has more than 10,000 downloads on Google Playstore.

CKS-HAU has also tapped vlogger Jericho Arceo to be the host of the tv and social media program entitled Aro Jericho which used to stream on Facebook and air on regional tv station CLTV36. Arceo is one of the most famous Kapampangan content-creators with 531,840 likes and 765,865 followers on Facebook, and 686,000 subscribers on Youtube.

“It has to be social media; it cannot be any other. I’m sorry to say but we have discarded or minimized the use of traditional media because they are no longer popular.”

Tantingco utters.

Tantingco says they are seeing positive response brought about by their efforts to keep the Kapampangan language alive. However, he believes these efforts will all be put to waste if the parents and other elders like Kaye, will not speak to the younger generation in Kapampangan.

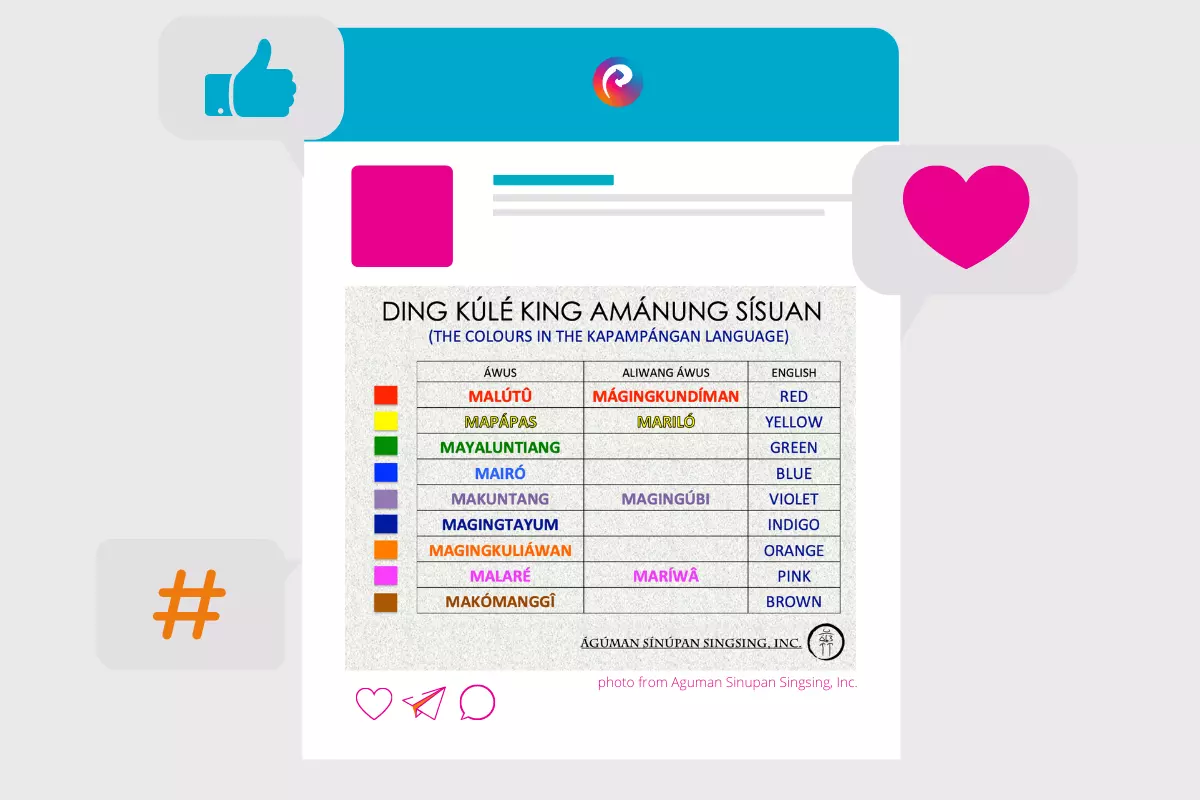

“We call our language Amanung Sisuan, or language suckled from the mother’s breast. We have to make our children speak it.” Tantingco ends.

-30-

*This article was originally written in September 2019 for the author’s school requirement at the Ateneo de Manila University – Master in Journalism Programme.

I’m Filipino-American born and raised, but I spent a lot years living and going to school in Pampanga when I was a boy along with my brother and sisters. Proud to have Kapampangan blood in me. Pagmaragul ku! As a hobby, I study a lot of Kapampangan history and culture. Especially on social media. I’m also trying to better my Kapampangan speaking, reading, and writing skills to when I was a kid there back in the day. I kinda lost that coming back to the United States. It happens to a lot of Pinoys who migrate to the U.S. Back in 2016 and 2018, Me and my wife visited Holy Angel University in Angeles and they have a great Kapampangan library museum or book store that sells Kapampangan literature and etc.

Hi JV! Thank you for sharing your thoughts. And thank you for inspiring all of us to better our Kapampangan too. I hope you can share with us your favorite materials in studying more about our culture. Stay safe Kabalen!

When I was at HAU, I bought one of their books: “100 most memorable Kapampangans” and on Amazon ( I was lucky to get that!) , I got a book about Andres Bonifacio ” In the blood” , a book about how AB’s roots can be traced back to Masantol, Pampanga due to many Bonifacios living there.